I have a piece of San Fernando Valley

history and culture hanging in my garage; it’s a portion of the original mural

that graced the main wall in the old Vitello’s restaurant on Tujunga Avenue in

Studio City. It’s a painting of

the Sicilian fishing village of Cefalu where the former owners, Steve and Joe

Restivo were born. They had bought

the original restaurant from Sal Vitello in 1977 and had the mural painted, and

it stayed there for 35 years. The

current owner then bought the restaurant and renovated it by opening up the

front wall to the street and making it feel more like a contemporary Italian

bistro. But when the wall came

down, so did the mural, and the best parts of the mural ended up with me.

|

| the original mural |

|

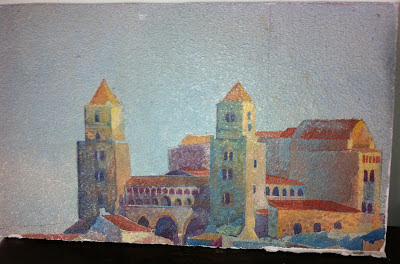

| my piece of the mural |

Things

must change, and Vitello’s is better for it in my opinion, but the old version

of Vitello’s had its charms. It was the classic red Italian restaurant - the

booths, the tablecloths, the sauce and the wine were all red, with old school

American Italian items on the menu that you only hear being ordered in a movie,

like Braciole (pronounced Brazhul), which is meat wrapped in meat.

No matter where you are from, there is

a version of this Italian restaurant in your hometown. Back in San Francisco where I grew up,

it’s Original Joe’s, which had branches throughout the City. When we lived in the Sunset District,

the family would head out on Sunday night to Joe’s of Lakeside for spaghetti

and meatballs.

The

San Fernando Valley gets a bad rap for having no culture, but we have plenty

going on. However, it’s also true that we tend to celebrate odd vestiges of

1950‘s through 1970‘s American Suburbia as if they were European Renaissance

Treasures. Thus, I love my piece of Vitello’s mural, as if it were a portion of

Da Vinci’s Last Supper.

The

old version of Vitello’s also had perfect kitsch. Photos of celebrities graced

the interior foyer, like Frankie Muniz and Garry Marshall. In Brooklyn, the same kind of

restaurant would have framed and signed photos of Tony Bennett and Frankie

Valli.

Vitello’s

became notorious nationwide in 2001, when Robert Blake’s wife Bonny Lee Bakley

was found shot dead a block away from the restaurant after the couple had eaten

there. Blake, a regular, had returned to the restaurant because he had

forgotten his gun in his usual booth.

When he went back out to the car, he says that he found her shot dead,

and he was acquitted of her murder.

My

wife Robin and I loved to go to the old Vitello’s and Steve, the more

gregarious of the two brothers, would always come by and say hello and

chat. I had read in the press that

they despised the notoriety, so it wasn’t until I felt that Steve had accepted

me as a regular that I dared to ask him about it. He pointed out which one was

Blake’s regular booth and from then on he’d seat us there -- right under an oil

painting of an Italian lute player and next to the closet with the vacuum,

broom and pungent cleaning supplies, covered up by just a red curtain on a

wooden rod. The seat in the booth

had come loose so if you sat on the edge it would pop up in back. But the wine

was decent, Robin loved the pizzetti, and I liked the fettuccine with

artichokes and steak.

In

2003, when we thought we were close to starting a family, Robin and I realized

we probably wouldn’t get to travel in a big way for many years so we should go

have an adventure somewhere.

However, it had to be right away. We had both finished shows early and

didn’t have our next jobs starting for several weeks, so we had to plan a trip

and go on a trip within days -- we just didn’t know where we wanted to go.

That

night we went to Vitello’s to make plans and Steve overhead us talking and

asked us where we were going.

“We

don’t know, where should we go?”

Robin asked.

“You

should go to Sicily,” Steve said.

“Where

should we go in Sicily?” Robin asked.

“You

should go to Cefalu, where my brother and I were born!” said Steve, and pointed

at the gigantic mural on the wall behind us. It looked like a make-believe medieval storybook town, on

the water below a towering mountain.

“Does

it really look like that?” I asked.

“Of

course it does! I’ll give you the name and phone number of my relatives there,

you must call them. When are you

leaving?” he asked.

We

followed Steve’s advice. We bought

tickets on Thursday and we went to Sicily on Saturday. We were there for two

weeks, winging the whole trip, getting lost constantly but eventually driving

around the entire island.

|

| Cefalu |

Sicily

is on the same latitude as Central and Southern California, so it looks and

feels the same in many places. The center of the island has rolling green and

yellow hillsides that look like the Salinas Valley, and the coast has towering

hills that crash down into the Mediterranean sea, like Big Sur. Many Sicilians came to California too;

some childhood friends came back to me when I saw their names on the town signs

-- Mazzarino, Randazzo, Trapani.

Sicilians

are tough people who give you the cold shoulder and a stare down for the first

30 minutes, and then after a meal and a drink they become your best friend and

want to spend time with you. We would arrive in a town and pick a restaurant,

and then after dinner the owners would insist that we come back and dine with

them every night while we were there and that they’d cook special meals just

for us. We complied, and the trip

was better for it.

Outside

Syracuse we stayed on a farm where we ate dinner with the family, and the

paterfamilias leaned across the table and said in broken English, “this

American war of yours, it’s a war about oil.” Suddenly

nervous, I grabbed the Italian English dictionary and did my best to make

conversation, and it worked. Three

hours later we were polishing off a bottle of limoncello, and they were refusrf

to let us leave the table.

Steve

was right; Cefalu was the best town (at least for us) and we were stunned that

the town looked exactly like the famous mural back in Studio City. The centerpiece of Cefalu is the

cathedral. It was built by the invading Normans who came to drive out the Moors,

during a time when every town was reinforced to withstand attack by the next

conquering army rolling through.

Thus the cathedral looks like a castle, which I’m sure it was when the

Normans first built it.

When

we returned to Studio City we went to Vitello’s to tell Steve about our trip

and he was crushed because we hadn’t eaten dinner with his relatives. We had called once but couldn’t

communicate well, we couldn’t reach the right sister, we didn’t think it was

crucial, and then we got occupied with our own vacation adventure -- but Steve

remained distant. After all, he is Sicilian. It took awhile for him to

forgive us, but he did.

When

the new owner decided to renovate, I begged him for part of the mural and he

kindly obliged. The

mural is just acrylic paint on drywall so it’s not built to last the centuries,

but I got some good pieces,including the section with the Norman cathedral that

rises above the town. Each piece is too heavy to frame and too big to hang in

the house, so I have them arranged on the walls of the garage. The pieces remind me of the Italian

restaurants from my youth, then of Sicily, which reminds me then again of

California, and we come again full circle. All I need now is a red booth.